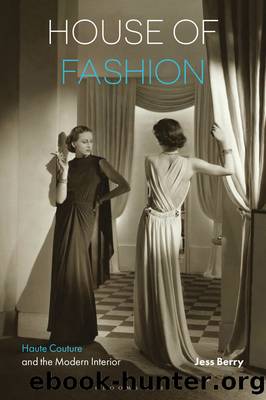

House of Fashion by Jess Berry;

Author:Jess Berry;

Language: eng

Format: epub, pdf

Publisher: Bloomsbury UK

Figure 5.5 Eileen Gray, Rue de Lota Apartment, 1921. © National Museum of Ireland.

Grayâs designs while modern in form often included sensuous surfaces and so were considered outside and deviant to the prevailing machine aesthetic characterized by the essentially masculine features of functional minimalism.35 Attitudes such as this have historically precluded Gray from the modernist canon epitomized by Loos and Le Corbusier, whereby womenâs designs were often prescribed with opposing socially determined attributes of femininity. As Lynne Walker argues, Grayâs approach to architecture and design, which focused on the comfort of the occupant, was often attributed to her femininity and attributes of instinct and emotion, rather than the masculine architectural ideal of rationality.36 I argue that Grayâs association with the fashion interior in the form of the Rue de Lota apartment presumably aligned her designs with femininity and, as such, overlooks her contribution to womenâs cultures of modernism.

Between 1918 and 1924, Gray renovated and redecorated the 9 rue de Lota apartment of Madame Juliette Mathieu-Lévyâmodiste (milliner and dressmaker), of the fashion house J. Suzanne Talbot. This commission was significant as it marked Grayâs transition from furniture design to the interior and architecture, where she designed walls, décors, lighting, and fixtures as well as furniture. The apartment, like much of the designerâs early work, combined modernist simplicity with material sensuality, where her use of textiles, hand-woven carpets, and throw-rugs made of fur and silk provide textual juxtaposition to geometric forms. Her approach to a modern, yet sensuous interior is perhaps partly belied by her view that design should follow from âinterpreting the desires, passions and tastes of the individual, [toward] intimate needs [and] individual pleasuresâ37 as opposed to how âexternal architecture seems to have absorbed avant-garde architects at the expense of the interior.â38 This sentiment, argues architectural historian Caroline Constant, is true of Grayâs work on Mathieu-Lévyâs apartment in particular, for it was âdirected more toward accentuating her clientâs individuality rather than the more general human qualities that characterize her later work.â39

Photographs of the Mathieu-Lévy apartment evidence how Gray used tactile materials to enhance the sensuous aspects of her designs in intimate spaces. For example, Baron de Meyerâs photograph of Mathieu-Lévy lounging on the Pirogue day bed for a perfume advertisement for Harperâs Bazaar in 1922 highlights a range of textures and surfaces (Figure 5.6). The reflective lacquered panel walls and the dark lacquered wood of the lounge are accentuated by soft-woolen textiles and shimmering silks. Mathieu-Lévyâdressed in a sequined dress and glittering jewelryâis posed in a manner redolent of Cleopatra, so heightening the appearance of the salon as a luxurious, yet modern backdrop to her glamorous and fashionable figure.

Download

This site does not store any files on its server. We only index and link to content provided by other sites. Please contact the content providers to delete copyright contents if any and email us, we'll remove relevant links or contents immediately.

Kathy Andrews Collection by Kathy Andrews(11323)

The remains of the day by Kazuo Ishiguro(8391)

Paper Towns by Green John(4794)

Spare by Prince Harry The Duke of Sussex(4786)

Industrial Automation from Scratch: A hands-on guide to using sensors, actuators, PLCs, HMIs, and SCADA to automate industrial processes by Olushola Akande(4596)

The Body: A Guide for Occupants by Bill Bryson(4581)

Be in a Treehouse by Pete Nelson(3647)

Machine Learning at Scale with H2O by Gregory Keys | David Whiting(3615)

Harry Potter and the Goblet Of Fire by J.K. Rowling(3608)

Never by Ken Follett(3523)

Goodbye Paradise(3446)

The Remains of the Day by Kazuo Ishiguro(3135)

Into Thin Air by Jon Krakauer(3129)

The Cellar by Natasha Preston(3077)

The Genius of Japanese Carpentry by Azby Brown(3036)

Fairy Tale by Stephen King(2944)

Drawing Shortcuts: Developing Quick Drawing Skills Using Today's Technology by Leggitt Jim(2938)

120 Days of Sodom by Marquis de Sade(2936)

The Man Who Died Twice by Richard Osman(2807)